TOPIC: Urban Economy, Sustainability

FORMAT: Research, Spatial Design, Object Design

WHEN: 2024

TEAM: Maryana Baran, Nazar Dnes, Tanya Pashynska, Yulia Rusylo, Yuliia Holiuk

RELATED PROJECTS: Sustainable Materials Laboratory, POLE

PARTNERS: Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation, supported by Switzerland and funded by Swiss Solidarity

Project SINO harmoniously continues our work with Roman concrete technology, which began in the Sustainable Materials Laboratory, which is now part of POLE. This time, the focus is on Kharkiv Oblast, a region heavily affected by building destruction due to Russian shelling. For our partners at Helvetas Swiss Intercooperation, this is also an experimental project within their new program dedicated to sustainable construction.

Initially, the team planned to restore a building damaged by explosions using sustainable design and architectural solutions. The original idea was to work remotely—developing the formula and solutions and sending them to the location for implementation. However, we realized this approach doesn’t align with our values. Understanding the local context, the community, and seeing the situation firsthand is essential. The chosen building was in a high-risk zone for shelling, so we shifted focus to a safer location. The Krasnokutsk community, which we learned about during a CEDOS workshop on social housing, offered several options. Eventually, we selected a public space with a natural spring, once actively used by the residents.

The community’s willingness to collaborate is equally essential when choosing a location. Without interaction, it’s impossible to develop genuinely relevant and practical solutions, as we cannot immerse ourselves in the daily context of life here.

The site is located near a local architectural landmark — The Singing Terraces (also known as the Haritonenko Terrace Gardens), an open-air amphitheater hosting various large-scale events. As a result, this area sees significant foot traffic, both from locals and tourists. For METALAB, such a location offers the opportunity to showcase our approach to sustainable materials and reuse publicly. It’s also a chance to demonstrate attentiveness to space design, encouraging people to engage with it and explore the topic of sustainability through direct experience. Ultimately, it’s an opportunity to test the self-sufficiency of the place — working with what is available on-site.

When working in frontline-adjacent territories, an extremely sensitive and thoughtful approach to the community’s needs is essential. These areas often attract numerous initiatives, many of which still need to fully assess the relevance of their projects. Frontline towns serve as a vital refuge for military personnel — spaces to rest, eat, and reconnect with family. These towns are relatively safer zones where intensely concentrated life thrives, with active businesses, services, and streets filled with both military and civilians. These are the people for whom we are creating this new public space.

In the Krasnokutsk community, a significant proportion of the population consists of internally displaced persons (IDPs), making up approximately half the residents. This is partly due to the preference for shorter relocations. Projects like SINO allow us to maintain contact with frontline communities and support them with our expertise. Through joint activities, we foster live connections. Our plan is to make the public space accessible to everyone, with a convenient approach to the spring, and build a kind of water pavilion (buvet) that incorporates sustainable practices and materials in construction.

In the SINO project, we emphasize working with sustainable materials and reuse.

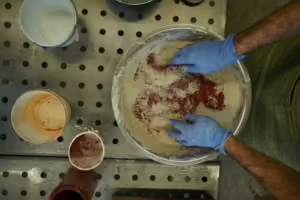

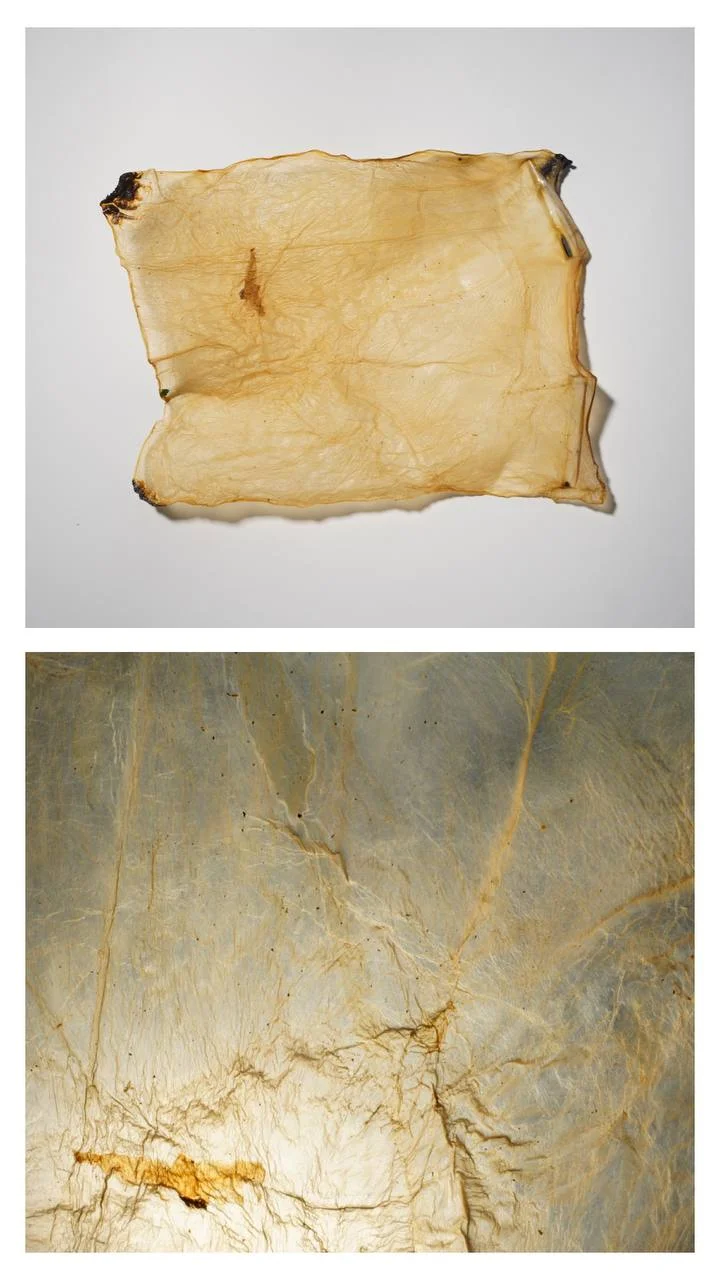

During the first workshop, we evaluated the site, brainstormed ideas to enhance its usability, and developed concepts to integrate it into the broader spatial vision. In the Sustainable Materials Laboratory workshops, we experimented with different recipes for Roman concrete—based on bricks from Kharkiv Oblast—and created eco-panels. These were then tested to select the most effective formula.

Meanwhile, work is ongoing at the site where the structure will be built. On our first visit, we discovered the water level had dropped significantly, and the spring was dry due to a blocked flow. Craftsmen dug through the area to locate the source while we conducted geodetic surveys, testing the water level and quality. The team installed a new structure to stabilize the water level and is now preparing the site for construction.

If the completed structure proves successful, we plan to scale the developed technology. It is vital to demonstrate to communities that there are alternatives to conventional building materials. Through various technologies, we can reveal the potential and value of local materials—proving that not everything dismantled from damaged buildings is waste. The most valuable element of the project is Roman concrete.

This initiative also highlights the potential of sustainable materials. The eco-panels will be used to construct internal partitions and will be tested in spaces within POLE. As a demonstration hub for sustainable approaches to design and architecture, POLE integrates and showcases these principles in its spaces and projects.

Through the SINO project, we are building a water pavilion around the spring, restoring access to water and creating a public space for gathering, relaxation, and exploration—a space for people to connect with sustainability in practice.